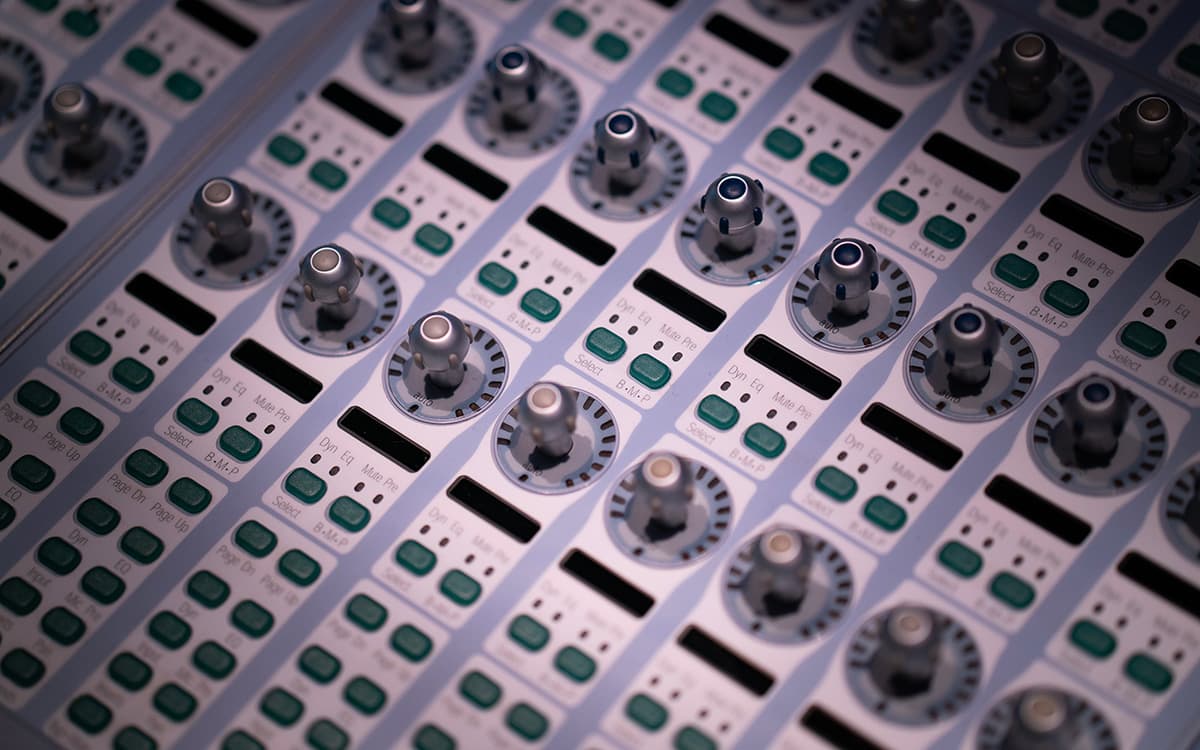

Inside a small recording studio in Manhattan, Keyon Harrold sits at the helm of a huge mixing desk. Blue led-lights flash and pulse upwards, illuminating Harrold as he plays his trumpet, layering the sound over a previous recording session. Reverberating piano trills and soaring brass build through the next few minutes – six minutes, to be precise. He tells me it was six minutes, because I ask, having been swept along with him in a trance.

Harrold, is one of New York’s foremost jazz musicians; the man whom Wynton Marsalis called “the future of the trumpet” as well as a skilled pianist and producer. He has two albums to his name, has recorded with JAY-Z, Beyoncé, Gregory Porter and Mary J. Blige, among others, and he’s a stalwart of the NYC jazz scene. He approaches his music as a craftsman; he takes his time, assesses the possibilities, and then produces something beautiful, fully fashioned and completely unexpected.

I caught an hour with him a few weeks ago, to learn a little more about what makes this man tick. Here’s what I discovered.

“I come in here to think. I don’t just walk in and say ‘I’m going to do a song today.’ I come off the street with an idea. I watch the news and because of this virus they’re going to fence off where my son lives. How do you make sense of that? So, I take the spirit of what I read or see and put the emotion together on the piano and trumpet. From there all of the work that I’ve put in, everything I’ve learnt as a musician, that technical part will take over. The emotion will turn into notes.”

“Malcolm Gladwell says, you do something for 10,000 hours and then you’re a master. But, once you get to that figure it’s all about how you forget it; so you can just be honest, a human, be a vessel to bring about change or to offer change. I try to apply that to music. Hopefully after some time recording we’ll have a song with a message. It’ll be a way to demonstrate what I’m feeling.”

“Even so, as an artist, it’s never about what I’m feeling. It’s about the moment when other people hear the music and how they feel about it. That’s what that message is. I’m the source and it’s all me before it gets mic-ed. Then, when the music gets mic-ed everybody is creating their own perspective; with their family, their friends, whoever. I try to be an open source of emotions as an artist. I want to give people some peace or some sort of understanding.”

“The world right now is so crazy to me. I can’t even write this stuff down like a movie. It’s not just ‘oh man, we had times like this when we were kids playing basketball, soccer, whatever.’ This time, the world as we know it will be different on the other side. Hopefully we can get through it in a way that is civil, peaceful and better than how it was before.”

“When I first moved to New York City I started studying at The New School. Wynton Marsalis is a mentor of mine so I was expected to be this straight-ahead jazz guy. But, there were a lot of cool guys at The New School. I met my friends Robert Glasper, Bilal, and a bunch of amazing musicians there. We would play straight ahead jazz but at the same time we were getting into all sorts of things like Hip Hop and lots of R&B. A turning point for me was when I started working with the rapper, Common. That opened me up to so many different worlds musically.”

“I also worked with Fela, Erykah Badu, D’Angelo and so many other people. I would go to Electric Lady Studios, and they’d be working on the records that we now know as classics. That was around ’99 to 2000-ish, so they’re all at that 20 year mark now. Mama’s Gun by Erykah Badu, D’Angelo’s Voo-Doo, Bilal’s 1st Born Second, Common’s Like Water for Chocolate, The Roots’ album. Everyone was doing amazing things. It was a renaissance time.”

“Before that, I’d say ‘no I don’t want to hear that, I don’t want to do that, I’m good!’. But those experiences helped me to realise that I could do different things; I can’t only play the trumpet. I can’t only play jazz. I started to figure out how to get my voice out there. To learn my voice so that I could talk to the world. That period really put me on a different trajectory.”

“I guess that’s the process of being a musician. You have to learn the trade from the squire to the master. You have to go through that whole process to learn the craft. You try to figure out what’s possible, what you want. Then you need to figure out someone that’s doing it, work with them, get great, develop a track record and then at some point you’ve got to go off, leave the nest and do your own thing.”

“I’m working on a new album right now. It’s called Soufo. Broken down it stands for ‘Sex. On. a U.F.O.’ Sex on, sex in, you know… It’s kind of risqué to hear. When people hear it they say ‘ain’t you a jazz dude?’. Yep, but it’s much deeper than that. It’s about that moment when you find somebody that makes you realise that you’ve never really had it before. People make love all over the place; on the train, on the airplane, at home, outside, wherever, even at the beach, but you’ve never done it on a UFO. So, the album is about when you find a person who puts you in this mindset and makes you think of some otherworldly things. It transcends the idea of the regular.”

“Sometimes, it’s hard to know when to stop working on a track, or an album. I’m trying to find those markers. A cut off point. Sometimes, I just need someone that I trust to tap me on the shoulder and say ‘come on, you know’.”

Listen to Keyon Harrold on Spotify or Apple Music.

(Photography by Elliot Hammer)

Geneva Custom Shirts: Old School Talent in New York

An artist’s guide to London, with Jonathan Lawes

Colour, depth and darkness: tailoring in The Great Beauty

Cotonificio Albini S.p.A. - Via Dr. Silvio Albini 1, 24021 Albino (BG) – Italy

Società con unico socio - diretta e coordinata da Albini Group S.p.A.

P.I. 01884530161 - C.F. 08743540158 - Iscritta al Registro Imprese di Bergamo - REA 244649

Capitale sociale sottoscritto e versato € 11.170.960