One of the first things that I learned about New York is that you’ve got to knock on a lot of doors. While this is the country of warm welcomes and “have a nice days’”, it’s hard to get below the surface. But, behind the door of Room 2A, 65 West 55th Street you’ll find a piece of the real New York.

At the back of the entrance hall is a wall covered in photographs of previous customers, everyone from presidents and a pope. There’s an array of actors and costume designers on show, who have entrusted Geneva with their period correct attention to detail; The Aviator, The Departed and Boardwalk Empire to name a few.

These days, Gene Athanasatos runs Geneva Shirtmakers. As a kid, he was always in his father’s workshop “picking up how things were done properly.” His father, Mike, retired a few years ago, but began his career working in the legendary men’s haberdashery, Sulka. Surrounded by some of the finest menswear in the world he learnt his craft under the tutelage of Sulka’s master shirtmaker, Chris Batsides. Then, after a lengthy term of service, Mike had the opportunity to set up his own workshop. And so in 1991 Geneva Shirtmakers was established.

A photograph of Mike now hangs on the wall behind Gene’s cutting table. Gene is busy. He’s behind a two-foot tall stack of orders surrounding his workbench. Seamstresses come up to his station every few minutes to pick up the freshly cut fabric and show him their work. He suggests that I stay a while to see how he works. He takes an order sheet from the top of one of the piles and says “this is how we do it.” He has an enthusiasm for his work that is rare. He pulls the roll of pattern paper across the table and slices it with a sharp blade.

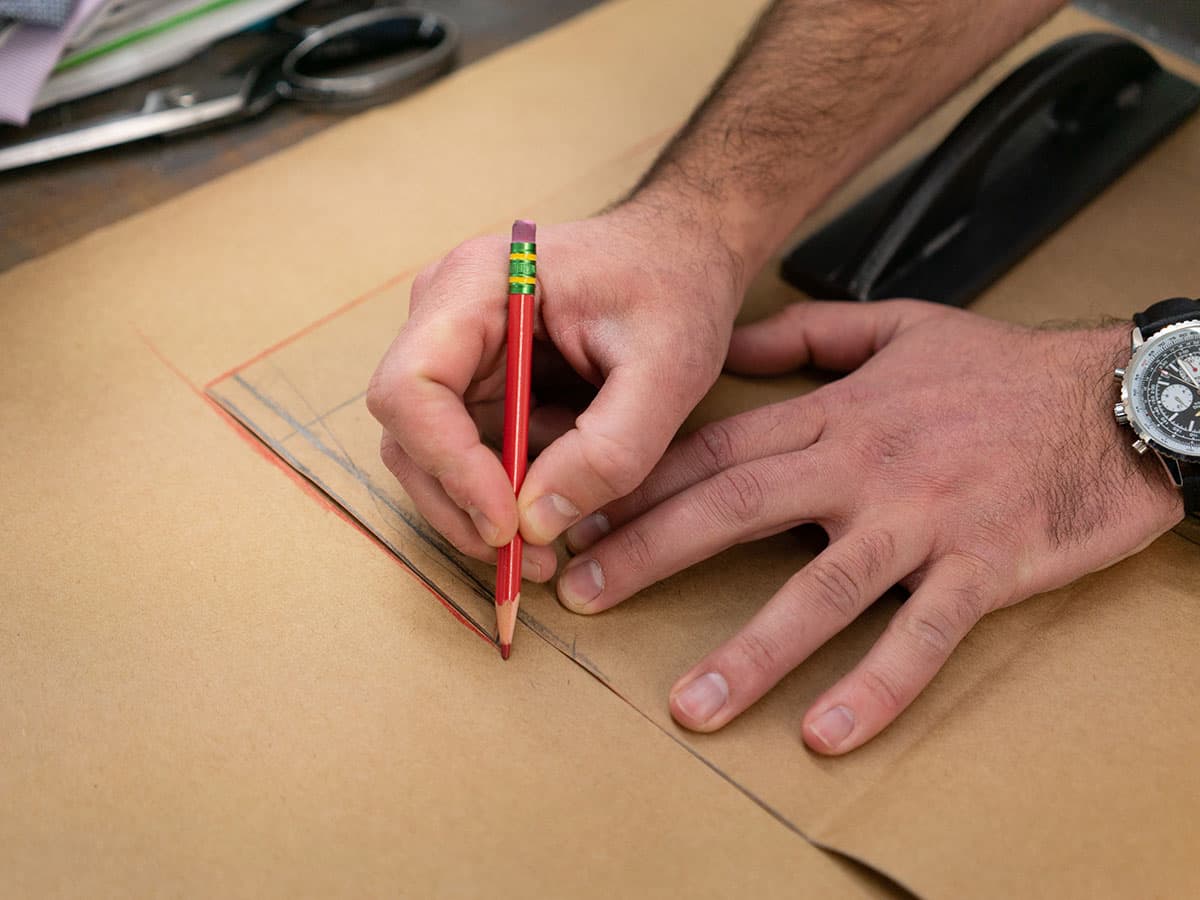

“The first thing you’ve got to know is that you can never have too many pencils.” There’s a pyramid of pencils stacked beside him that are, one by one, being fed into a pencil sharpener. “I’ll be here all day working on new patterns and it’s important to be precise. I use graphite for the initial shape and then red for the lines which need to be cut. It’s not worth making mistakes.”

I watch Gene work his way around the pattern paper with various curves and rules. He measures carefully, notes down some arithmetic directly on paper and checks it again before making his final red marks. Slowly the shape of the shirt is revealed. I could watch this process for hours – there’s something very peaceful about watching a craftsman work. It’s almost meditative.

The difference between a good shirt and a great shirt feels like miles of distance when you’re wearing one, but the accuracy to which custom garments need to be cut is remarkably fine. Gene carefully works from the base template before refining his pattern freehand – tailors call this skill ‘rock of eye’ and there aren’t many artisans who still practise it today. Each new line reveals a trick or technique learnt though repeating and refining the process over thousands of patterns. It never ceases to amaze me that a few measurements and a two-dimensional pattern will turn into a three-dimensional object that will fit one person perfectly.

The final step of pattern making is to cut it out or ‘strike’ it. Gene uses a sharp scalpel-like knife to trace his red lines. “It’s all about precision. You can’t use scissors on something like this and expect to get the shapes that you want. I’d just be picking up the paper and moving it every two seconds.” Gene contorts his arm and wrist to allow the blade to move freely. The cut pattern pops out of the paper almost before I realise he’s finished.

Gene moves over to the next bench with the pattern in hand. He presses, marks and cuts the shirt’s fabric before folding it into a neat package. He shows me the tricks of pressing. For a moment it looks easy. Then I realise he is matching the stripes of fabric across different panels of the shirt – using a system of minute notches in his pattern to align different pieces of cloth. He then takes into account how the fabric will move with the knife. Some minutes later, the shirt is cut and the pattern is carefully folded into an envelope and filed away. The bundle of fabric moves through the workroom to a seamstress, who will sew the shirt in time for the client’s first fitting.

Among the whirring sewing machines and pristine shirts hanging on rails are some dinosaurs like the old steam press in the back room. Gene lays down a half-made collar and the machine clunks in action. “You can’t get these anymore. They were all custom made decades ago,” is his only comment. The sharp hissing subsides and the jaws open to reveal a pristine collar. “It’s not easy to keep this thing going but you can still learn something every day.”

Every house has its own style and a set way of doing things, but nobody in The Big Apple makes shirts quite like Gene. There is something in the process that you can’t put your finger on. At Geneva, you’re not paying for the unnecessary frills. Don’t expect champagne at the door or perfumed packaging. You’re here to get what matters; good guidance and access to refined talent. Geneva Shirtmakers make an honest shirt. For me, it’s worth the price of admission just to see that this can still happen in New York.

Discover more at genevacustomshirts.com

(Photography by Elliot Hammer)

Turnbull & Asser’s Quiet Evolution

Michael Hill on his father’s cardigan

Beyond Blue and White: Some fresh thoughts on formal shirts

Cotonificio Albini S.p.A. - Via Dr. Silvio Albini 1, 24021 Albino (BG) – Italy

Società con unico socio - diretta e coordinata da Albini Group S.p.A.

P.I. 01884530161 - C.F. 08743540158 - Iscritta al Registro Imprese di Bergamo - REA 244649

Capitale sociale sottoscritto e versato € 11.170.960